Archery’s greatest Olympian is hiding in plain sight

Was it a loss, or a rite of passage?

Junior Sizemore stormed off the field in disbelief, his head held low, oblivious of the geriatric who had just beaten him.

It was the second stage of the USA’s Olympic trials in Atlanta, Georgia. Sizemore, a precocious teenager brimming with potential, had his sights set on representing his country at the Atlanta 1996 Olympic Games.

A loss to an anonymous old man threatened to derail those plans.

“What’s wrong, Junior?” 1988 Olympic Champion Jay Barrs asked, walking up to him. “Why the long face?”

“Aw, that old guy over there just beat me,” Sizemore said, gesturing to the source of his misery.

Barrs still smiles at the memory.

“The guy he was pointing at,” Barrs said, “was Darrell Pace.”

If younger generations were unaware of Pace in 1996 – eight years after his last Olympiad – there’s little hope of them knowing now.

But they ought to.

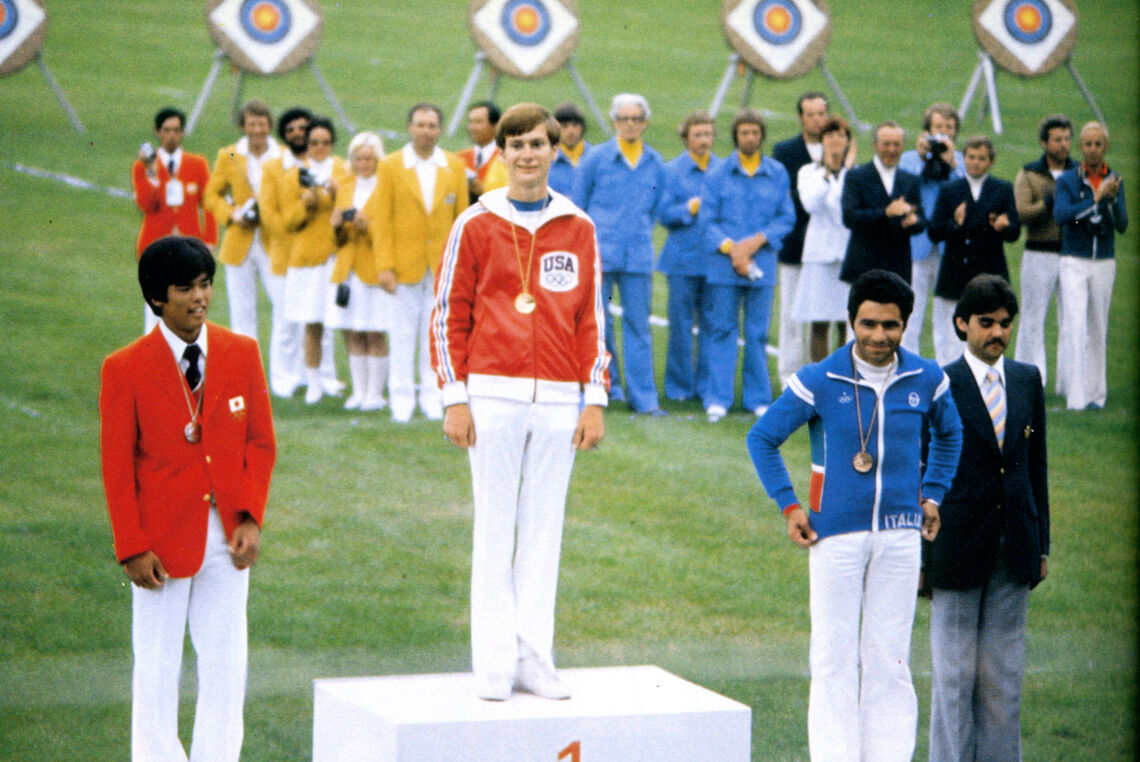

One of the most decorated archers of all time, Pace’s list of accolades stretches to near-mythical proportions, including his status as the only Olympic archer to win two individual gold medals in the history of the Games.

“Who was the last person who owned every single world record at one time?” Rick McKinney asks rhetorically. McKinney was one of Pace’s teammates and a decorated archer in his own right.

From his peers, there is no shortage of admiration.

“You wouldn’t believe how many times Darrell and I would show up to a tournament, and the first thing that would come out of peoples’ mouths was, ‘well, looks like we're going for third place’,” Rick continues.

It wasn’t just the certainty of Pace’s victories that set him apart, but the dominance in which he claimed them.

He obliterated the field to capture his second individual gold medal at the Los Angeles 1984 Olympic Games, shattering his own Olympic record from Montreal in 1976 to demonstrate his supremacy in the sport.

The title was so certain that he took a lunch break midway through the final day to meet with the press. McKinney, who had beaten Pace at the World Archery Championships the year prior, finished 52 points behind over the double FITA (now the double 1440 Round) to win the silver medal.

“There would be times when he set a world record one day, and then two days later he’d beat that world record again by another point,” McKinney said. “He’d do it constantly, and it would drive you nuts.”

He laughed.

“You’d just sit there thinking, ‘well, how do you beat him?’ How do you beat him when he sets his own standards? We were all trying to get ahead of him, but it was really hard.”

For all of his success in 1984, Pace said the victory brought back many of the bitter feelings he felt when the USA boycotted the Moscow 1980 Olympic Games.

At the time, Pace was considered a shoo-in for a gold medal. His competition was weaker than it had been four years earlier, and it seemed certain that Pace would defend the gold he won in Montreal. (His score then was more than 100 points higher than Tomi Poikolainen’s winning result in 1980.)

Instead, he was denied the opportunity.

“I never liked politics in the Olympics,” Pace said. “Athletes like to compete. We don’t care about politics. We just want to compete to see who the best is.”

Pace found the boycott so upsetting that he considered retiring. But as a member of the United States Air Force, he was unable to voice any sentiments that would contradict his commander-in-chief.

“No comment, no comment, no comment,” Pace recalled. “That's all I could say, because I was in the military.”

Had the USA not boycotted those Games, Pace could have further cemented his legend. Archery was reintroduced to the Olympic programme in 1972, and victories in 1976, 1980 and 1984 would have given him three of the possible four medals in the sport’s Olympic history.

“Everyone says it probably would have been three,” Pace said. “Me and Edwin Moses.” Moses was the USA’s track and field star whose string of gold medals was also interrupted in 1980.

“There’s a Trivial Pursuit card that says, ‘only two people won Olympic gold in ’76 and ’84. Who are they?’” Pace said fondly. “Everyone always says Edwin Moses, but no one knows who the other one is.”

Pace nonetheless expresses gratitude for a remarkable career that spanned more than two decades.

But he has also detached himself from the sport’s establishment and resists others’ admiration and praise.

“It wasn’t about trying to pulverize your opponent,” Pace said when asked about his large margins of victory. “It was just trying to build a cushion; 1976 was by 69 points, 1984 by 52 – those were just cushions.”

Talking over the phone from Cincinnati, Ohio, a gravel-voiced Pace, now 62 years old, sounded fully committed to his post-archery life, which includes softball, bowling (he’s rolled multiple 300s) and a career working for the USA’s Department of Natural Resources.

But he still follows the sport with zeal.

Pace works for USA Archery as a contractor setting up targets and the announcement system at tournaments. He’s a fixture at USA Archery’s youth tournaments and he also offers his services coaching.

The next generation of archers might not know who Pace is, but he is still invested in helping them succeed.

“The funny thing is how many people don’t know it’s Darrell Pace out there, the two-time Olympic gold medal winner, setting up the field for them,” McKinney said. “There’s definitely a level of anonymity.”

Pace, for his part, prefers it this way. He keeps most of his awards in storage, and only a few are displayed in his house. Similarly, McKinney said, it took years for Pace to get inducted into the Archery Hall of Fame because he couldn’t be bothered to submit the paperwork necessary for them to consider his name.

“He doesn’t come to the events because he’s a double gold medallist,” explained Sheri Rhodes, events manager for USA Archery and Pace’s former coach. “He comes to the events because he wants to keep archery alive and keep it growing.”

His understated nature, however, does lead to moments of confusion. Running events is hard work. The days are long, and the work is often thankless, arriving before dawn in the morning and leaving late at night.

During any brief windows of time between rounds, Pace has been known to nestle into a vacant golf cart for a quick nap.

“I remember hearing someone say, ‘who's that guy in the golf cart? Is he sleeping?’” Pace laughed. “I figured I’d earned that. It was the first 10 minutes I’d had all day.”