An San’s Robin Hood: The moment mixed team made its mark at the Olympics

This month, World Archery is celebrating Mixed Team March ahead of the upcoming outdoor season.

While mixed team competition had already been fixture in international archery since the early 2000s, its first moment in Olympic history would always be important.

There was originally hope that it would be part of the Games at Rio 2016, but this did not happen. Its first day in the Olympic spotlight would be a historical milestone for the sport – and would feature one of its most dramatic moments.

The troubled Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, a year delayed, would provide the backdrop. 24 July 2021 was a blazing sunny Saturday in Yumenoshima Park with the cicadas screaming and thermometer hovering in the mid-30s all day long.

It would be the first medal event of the archery competition. In that difficult Games, held without spectators, it would become a TV spectacle only.

Sixteen pairs from sixteen nations got to try their luck in the main arena for the mixed team competition, chosen from the top scores from the ranking round and ultimately permed from a possible thirty possible pairings who shot the day before.

Three quarters of the field would fall in the first two rounds, and there were upsets; Great Britain opened well against the rather more fancied China, but then shot indifferently against Mexico to leave at the quarterfinal stage.

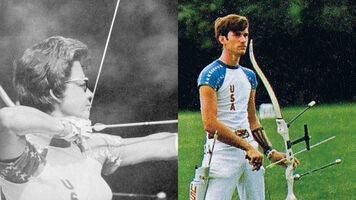

Chinese Taipei unexpectedly exited quickly to India; Germany and Russia left immediately, as did a sub-par Italy, and perhaps the biggest shock of all: the USA going down to a tightly-wound Indonesia, who had been looking like a threat for months. Brady Ellison left the press zone with a breezy comment of: “I’ll try not to smash something.”

Of course, Korea were in the mix, and the semifinal between Kim Je Deok and An San and Mexico’s Luis Alvarez and Alejandra Valencia would be remembered – forever. In the second set, An’s second arrow would smash through the back of an arrow of Je Deok’s already on the face, an event known as a ‘Robin Hood’.

Some amateur archers have experienced this shooting at shorter distances, but to happen at 70 metres, in wind, outdoors, on such a historic day, is unprecedented. It is also thought to be the first time the phenomenon has ever been captured on camera.

Why is this event called a ‘Robin Hood’? As with so much attached to or named after the 13th century English outlaw, including his very existence, it is something added on after the fact – in this case, a fictional 19th century legend about splitting an arrow on the target face added by the author Sir Walter Scott. (People also argue about whether it should be called a Robin Hood if you hit one of your own arrows, or whether, like in Tokyo, you hit someone else’s.)

The chances of a Robin Hood even happening in a 70-metre recurve competition are extremely rare, especially as both archers were using Easton X10 arrows, which are ‘barrelled’ (the end is thinner than the centre). George Tekmitchov, the engineer who designed the X10, made a calculation that An San’s shot must have been no more than 0.2mm away from the dead centre of Kim Je Deok’s arrow – and almost perfectly aligned.

“I said sorry to him afterwards,” An San joked during an interview after the Games, calling it the highlight of a competition that she would ultimately go on to dominate.

But it was a moment of metaphor as much as anything else: the rarity, the perfection, and the subtler, symbolic demonstration that there was no discernible difference between the skill of the man and the woman in the pairing.

Minutes later, Korea then went on to win the final against the Netherlands, although this was also not without a little drama. The Dutch pairing of Gaby Schloesser and Steve Wijler opened with a 38 to a twitchy Korean total of 35, and suddenly another outcome seemed possible. It took a furious, vocal performance from Kim Je Deok to drag the match back to level terms, with An San not at her imperious best.

With Korea up 4-2, the Netherlands opened the fourth set with a nine and a 10. Korea replied with two tens. Then Wijler and Schloesser stepped right up with two tens and a total of 39; the sort of statement that says “we’re going to a shoot-off”. (Schloesser’s 10, under immense pressure, deserves special applause.) But as so often, Korea had just enough in the tank to get the match closed out.

Asked about the match afterwards, Je Deok startled the assembled reporters with the Eric Cantona-esque: “Yesterday I had a dream, and there were several snakes in my dream. I thought it was an auspicious dream.”

“I remember standing on the podium with An San and hearing our national anthem – it was surreal,” he said. “We worked so hard to get there, and to make history together was something I’ll never forget.”

The mixed team competition in Tokyo was so important for the sport that IOC President Thomas Bach was present to watch and help hand out the inaugural medals. It also broke the ice on an Olympic archery competition held in the most trying circumstances.

It added something to national stories too: Kim Je Deok, at 17 years and 103 days became the youngest male athlete representing Korea to claim an Olympic gold medal (in any sport), breaking the record held by Im Dong Hyun who was 18 when he won gold in the men’s team in Athens in 2004. Gaby Schloesser, who competed for Mexico before she became a Dutch citizen, became the first female archer representing the Netherlands to claim an Olympic medal.

The ‘Robin Hood’ arrows, now permanently married together, are on display in the Olympic museum in Lausanne, the Olympic capital, having been donated by the archers to the Olympic Foundation for Culture and Heritage. Volunteers from the foundation constructed a special box to ship the fragile pair of arrows back to Switzerland.

The mixed team competition, long-mooted and finally delivered, stuck the landing for what the international federation and the IOC wanted: a diversity of nations involved, a very public commitment to equality, and a new and exciting medal event. And it was marked by a moment of symbolism and perfection that summed up its meaning and potential.