Professional athletes: Archery at the Olympics from 1996 to 2020

Previous articles in this series have explored archery’s return to the Olympic Games in 1972 and its amateur era from 1976 to 1992.

In 1996, the Olympics returned to North America for the largest Games yet held. Archery, along with track cycling and tennis, was held in Stone Mountain Park, a picturesque site 15 miles outside the city of Atlanta.

The wider event is perhaps best known for garish commercialisation (which ultimately led to the strict branding rules still in place today), a few organising mishaps and a terrorist incident, rather than its legacy of sporting excellence.

But the archery competitions offered up one of the greatest surprises in Olympic history.

A qualification and quota system was used for the first time in Atlanta, with the number of archers set at 128 – 64 men and 64 women – where it has remained ever since. This made archery one of the first Olympic sports to achieve equal gender participation at the Games.

The qualifying round was shortened from 144 to 72 arrows – all shot at 70 metres. After qualification, the competition went to matchplay. Individual matches in the first three rounds were decided on total score over 18 arrows and quarterfinals on over 12 arrows.

Ukraine’s Lina Herasimenko and Italian man Michele Frangilli seeded first. Frangilli set a new Olympic record of 684 points and was widely regarded as the favourite. Herasimenko’s score of 673 astonishingly stood as an Olympic record for 25 years, until the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games (held in 2021), when it was finally beaten by Korea’s eventual triple-gold-medallist An San.

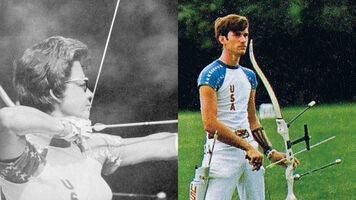

One archer of whom little was expected was Justin Huish, who had scraped into the USA team as the third man. He was 19 years old, sporting earrings, a ponytail and wraparound shades under a reversed baseball cap. He looked more like a skateboarder than an archer.

Huish’s parents owned an archery shop but he hadn’t shown much interest in the sport, regarding it as “boring”, until he picked up a bow at age 14 and found he had a talent for it.

“[US coach] Lloyd Brown told me from one of the first few times I met him that I could make the Olympic team someday,” he said in 2021. “I just laughed at him.”

Coached by Brown, Huish entered the US trials for the 1992 Olympics but finished a long way off the pace.

“I just never put myself in that place, with Jay Barrs and Darrell Pace and all the greats. I just never thought I could ever beat them at that time,” he explained. “But in ’93, I started shooting the scores that those guys were shooting.”

In 1995, Huish moved to Chula Vista to practise full-time at the Olympic training centre, which had recently opened a residential programme for archers.

“I filled out an application form because I didn’t really know what I was doing with my life,” he said. “I knew I wanted to shoot, but I still didn’t really equate that the Olympics were attainable.”

Alongside fellow residential athletes Rod White and Butch Johnson, who all lived together in one room at some point, Huish buckled down and worked, winning the national championships in 1996. The three men would eventually comprise the US team for its home Games in Atlanta.

In the build-up to the Olympics, the brash Californian teenager caught the eye of the press and Huish even appeared on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno.

“The questions were about winning gold medals when I just didn’t want to lose that first match. Everything after that would just be gravy,” recalled Justin. “Making the Olympic team is one thing. But, you know, actually winning the stupid thing? I mean, no way!”

Despite a lack of any prior international success, the teenager seeded a strong ninth over the qualifying round at Stone Mountain. With domestic support behind him, Huish began to tear through the men’s field. In footage of the event, you can see him growing in confidence with each match, with each win, roared on by the home crowd.

“My mind was just saying: ‘Hey, I’m an Olympian. I’m just here for the experience.’ I think that definitely helped tone down any pressure that I was putting on myself because no matter what, I had already wildly exceeded my expectations. It just felt national,” he said.

Somehow, through a quirk of fate, Huish had been assigned the number one as his athlete identifier – out of all 10,300-plus at the Games.

“Everything that happened was just like it was meant to be. It felt like I could have shot my arrow behind the target, in the opposite direction, and it would have boomeranged around and still come and hit the 10-ring. Like I could do no wrong.”

Huish beat six opponents in a row, edging out top seed and favourite Frangilli in a quarterfinal double-shoot-off and then eventually defeating Sweden’s Magnus Petersson for gold.

His world suddenly exploded.

It was three in the morning before Justin had finished the round of media interviews and got to bed, despite having to wake up and shoot the men’s team eliminations at seven the next day. (In 1996, the men’s and women’s team finals were shot on the same day – the last day of competition.)

“I should probably have said, ‘no, I can’t do all these things’, but it was just a whirlwind. I didn’t know any better,” said Huish.

The US men’s team – Justin, Rod and Butch – rose to the challenge, even if Huish claims his teammates carried him, exhausted, through the first two matches. He found the energy to eventually face the Korean men in the gold medal match.

“When I needed to come through, I did,” said Huish.

The trio shot 251 points in all four rounds of matchplay – in the then-27-arrow matches – and eventually beat Korea by two, although there was some nerve-wracking measurement required in the final end.

The victory in Atlanta remains the US men’s only team gold at the Games to date, although they did also collect back-to-back silver medals in the event in 2012 and 2016. Huish became the first male archer to ever do the double – both individual and team gold at the same Games. It wouldn’t be matched until Ku Bonchan in 2016. And Huish still remains the only non-Korean archer to take more than one gold at a single Olympics.

Korea’s women were already firmly entrenched in Atlanta. Kim Kyung Wook won individual gold and the women delivered a then-third-consecutive steamroller performance in the team competition.

The media swarm around Huish didn’t stop for a long time.

“In the US, archery gets zero love,” he said. “They don’t report on other sports, it’s pretty much baseball, NBA and NFL and that’s it.”

“But because I had the ponytail, hat on backwards and was wearing sunglasses, and not your prototypical [archery] athlete, it crossed over quite a bit into the mainstream media. Normally, you might get a mention on, like, the fourth page of USA Today. I was front page and getting all the big interviews.”

“I got to ride with vice president Gore from the basketball game to the closing ceremony, go to do a lot of stuff that would usually be left for the guy who wins the 100-metre dash.”

Huish remained on the US team until 2000 when his career and life took a sharp turn. He withdrew from the Games in Sydney after being caught selling marijuana, eventually receiving a four-month prison sentence and a two-year ban from the sport.

Nearly 20 years later, Huish made a return to serious recurve archery, working his way around the US circuit and back up the rankings. To date, he’s not ruled out a run at a potential second Games.

“The Olympic rings… for a lot of people, you know, it’s the mountain top. For some people, they’ve been training since they were four years old, and that’s all they cared about all their life,” said Huish. “But there might be two different ways to get there. I kind of took the back roads, I guess.”

In many ways, Justin Huish personified the lucky amateur, showing up essentially out of nowhere and giving one of the most thrilling performances yet seen on the Olympic stage – and subsequently being thrust into an increasingly professional spotlight. After a century of strict amateurism at the Games, the job of an Olympic Champion, even an Olympian, extended far beyond the competition field.

The Games in Sydney are often held up as the model for a modern Olympics. Sports-mad Australia put on a spectacular show and wild success across the board re-invigorated a slightly stagnant Olympic movement, inspiring new bids from potential host cities the world over.

Most archers perform the best at their very first Olympics. (It’s true.)

When Simon Fairweather, of Strathalbyn in the Adelaide Hills, won the World Archery Championships in Poland in 1991, his future in the sport seemed assured. He was 22, already an Olympian and was sponsored as a full-time athlete. What followed were nine years of frustration and unfilled expectations, with Fairweather struggling to regain the form that booked him the world title. His performances in Barcelona and Atlanta had been anonymous. He almost quit the sport more than once.

By the time he got to Sydney, it was his fourth Games, he was already 31 years old – when most previous Olympic Champions had been sub-20 – but he’d spent two years training full-time under then-Australian-coach Kisik Lee, who was one of the first but definitely not the last Korean coaches to export their expertise.

Lee’s time as a national coach in Korea had brought 16 Olympic medals – eight of them gold – and he was convinced Fairweather still had what it took.

Simon’s day of destiny came on 20 August 2000. In the gusty winds of Homebush Bay, he equalled the Olympic record for the 18-arrow match in his first round.

“I don’t remember doing anything wrong. I was very disciplined in following my routine. I barely shot a bad arrow in all my matches,” he said in 2016.

“Finals are like a staring competition. That day I was the one who didn’t blink. It was a matter of staying with the routine and excluding thoughts of other things. It’s not a time for savouring the experience and looking at the spectacle that’s unfolding around you.”

“I just told myself to keep my mind on my job, my routine. After that would be time for thinking about what it still means.”

In the gold medal match against the USA’s Vic Wunderle, Fairweather nervelessly shot 10, 10, nine to set up a lead… and never looked back, winning resoundingly, 113-106. Simon would also shoot for Australia at his fifth Olympics, four years later, before retiring and going into business.

Wunderle, for his part, made two more top-eight appearances at the Games and still shoots today.

The archery competitions at the Athens 2004 Olympics were fraught with problems – which began years prior and continued until the very last moment. Even the night before the first scoring arrows, things looked uncertain. But the event was finally held in one of the greatest venues in the history of the Games: The Panathenaic Stadium, home of the ancient Olympics.

Credit for this goes to the late Beppe Cinnirella, who called securing the location one of his proudest achievements as World Archery secretary general.

At one point, the organisers threatened to hold the archery events on an airport runway. Beppe persuaded them to divert their car via the ancient stadium.

“We stopped and had a deep look. At the meeting, we proposed the Panathenaic and obviously the answer was, ‘no chance’,” he recalled in 2017. “Slowly we overcame all the obstacles and finally we got it approved. And I still think the choice of the Panathenaic, which was my idea, was one of the best things that happened to the sport, for FITA, for the future.”

The splendour of the archery competition against the gleaming white marble became one of the key visual images of that Games, which saw an unexpected victory for Italian man Marco Galiazzo and a silver for Japan’s Hiroshi Yamamoto, an astonishing 20 years after his bronze at Los Angeles 1984.

Park Sung-Hyun, widely regarded as one of the greatest archers of all time, won the women’s title as her Korean teammates – Lee Sung Jin and Yun Mi Jin (the returning winner from Sydney) – completed a sweep of the individual podium, and then took an(other) easy team title.

Not since Darrell Pace’s dominance of the men’s field in the late 1970s and early 1980s had there been such a head-and-shoulders favourite for back-to-back Olympic titles. (Pace ultimately won his two golds eight years apart with the US team’s boycott of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow.)

But Park, who became the first recurve archer to break 1400 points on the 1440 Round in 2005, was the favourite to repeat in 2008.

The Olympics were back in Asia. China was finally awarded the Games for the first time, starting an era of major multisport events in the country. Beijing built not one but two temporary archery arenas in a major new sports park, erected specially for the Olympics, with each staging eliminations concurrently.

The effort was well rewarded.

In 2008, Korea’s women had won six straight individual titles at the Olympics. China’s Zhang Juan Juan was in no mood to allow that dominance to continue.

“I felt really pumped up when I was up against the Korean archers,” said Zhang at the time. “I had put in a lot of effort to compete with them. Even if I were to lose, I wanted to intimidate them with my performance.”

Zhang seeded just 27th but proceeded to scythe through the women’s field – including all three Koreans.

She beat Joo Hyun-Jung by five, 106-101, in the quarterfinals. (Incidentally, this was the first Olympics at which every match was decided over 12 arrows, rather than the 18 for the early phases as had been used previously.)

Then fell Yun Ok Hee, one of the most successful internationals of the late noughties, 115-109.

Park, the favourite, had shot that score – a new Olympic record – just a few rounds earlier. She was into the final, her second consecutive at the Olympics, too. But the outcome in the rain-soaked arena was no longer certain.

The Chinese archer shot a seven in the first end. But at the end of the third, Juan Juan was a point up. A nine with her last arrow sealed victory.

As with Fairweather’s win in 2000, Zhang credited her success to laser-like focus.

“I had found this incredible level of concentration and was just totally immersed in my own mind. Sometimes I couldn’t tell if the match was actually finished, because I was totally focused on my game,” she said. “I knew my opponents were very strong, but I was totally confident that I could do better than them. I did not realise until much later what I had actually achieved.”

Zhang remains the only non-Korean archer to win the women’s title at the Olympic Games since the nation’s competitive emergence in 1984.

Professionalism had begun to change the sport outside of the Olympics. Between Athens and Beijing, the Archery World Cup was launched. The elite competition circuit provided a regular competition outlet for athletes outside of major multisport events and world championships. Commercial and broadcast opportunities were starting to emerge.

London was the first city to host the Olympic Games three times.

Lord’s Cricket Ground morphed from the sacred ‘Home of Cricket’ to the ‘Home of Archery’ for a few weeks in the summer of 2012. It was the first time that the Olympic archery events would be held in another existing sporting venue.

Archers shot from just in front of the old pavilion, over the hallowed turf, towards the iconic modern media centre.

With huge temporary stands erected on the outfield of the cricket pitch, the 6500-capacity arena was a sell-out. (Spectators even turned up to watch the closed-doors qualifying rounds having fallen victim to a ticketing scam.) The stadium was packed to the rafters and the atmosphere was electric.

London saw the introduction of the set system for individual matchplay. (The team competitions remained on cumulative score.) Another change was the scheduling of both men’s and women’s early-round eliminations in the same session, streamlining the schedule and defining clear finals days – a move that will remain in place until at least Paris 2024 and probably beyond.

Korea won three of the four available medals – but the country’s men were relegated to bronze as Italy beat the USA in perhaps the most exciting Olympic team final ever witnessed.

Aida Roman and Mariana Avitia put Mexico on the archery map, taking women’s individual silver and bronze, setting the stage for the country’s ongoing competitive rise. It was the fruit of an extraordinarily successful elite programme.

Ahead of them on the results sheet was only Ki Bo Bae, who enjoyed wild popularity following the win.

She was the seventh Korean woman to be named Olympic Champion. For all the female squad’s dominance, prior to 2012, the Korean men had never crested the mountain, taking silver medals three times (in 1988, 1992 and 2008) and bronze once. But on the final day of the Games, 13-year international veteran Oh Jin Hyek achieved what none before could.

He dropped Ukraine’s defending champion Viktor Ruban in the quarterfinals, survived Dai Xiaoxiang of China in a semifinal shoot-off and then beat Japan’s Takaharu Furukawa to gold.

The success of the Olympics in London was followed by a financially-troubled Games in Rio de Janeiro. The first Olympics in South America were awarded in a period of plenty for Brazil – but by the time they took place in 2016, the landscape was vastly different.

Archery took place in one of the city’s most iconic thoroughfares, the Sambodromo, brought to life once a year for the world-famous Carnival.

Unlike the Olympic Park, which was in a suburban neighbourhood in the west, the venue was sandwiched between favelas in the city’s downtown. It was, however, perhaps the most atmospheric venue of all, with a backdrop of the Corcovado mountain and the statue of Christ the Redeemer. Across seven days of competition in wildly variable weather, the unique spot left an impression.

It was hoped to introduce the mixed team in Rio – but challenges ahead of the Games prevented it.

The competition followed the same format as London but finally brought the set system to the team events. It was also the first Olympics to utilise electronic scoring, made possible by huge laser frames erected around the targets, the first iteration of automatic arrow spotting that was implemented at World Archery events.

Korea – for the first (and to date only) time – took every available gold medal.

It was the apotheosis of a system funded to produce Olympic results, even if neither of the individual winners, Chang Hye Jin and Ku Bonchan, went into the competition as favourites. And even if neither is still considered among the pantheon of true greats.

It felt almost as if a bubble had burst.

Sure, archery was professional. But Korea was the most professional. At an Olympic Games in which the village, where athletes were living, was at least a 45-minute drive away, the team had installed a secret rest facility close to the venue.

A squad so clearly better organised, better funded and better backed had arrived… surveyed… and conquered.

Before 1992, archery was at risk of Olympic exclusion, its competition format in dire need of evolution to maintain relevance in a rapidly-evolving and television-first environment.

By 2012, the head-to-head format, a preference for iconic venues, the launch of the Archery World Cup and, finally, the set system, had earnt the sport serious respect. After London, archery’s financial status was upgraded – meaning it would receive a larger share of revenues from the Olympics. The trend continued through Rio. Media numbers and interest figures were higher than other ‘better-known’ Olympic sports.

With the mixed team finally added for Tokyo, optimism was high for Tokyo. It would be the fourth Games in Japan (including two in the winter) but the fourth to include archery.

In Yumenoshima Park – dream island park – on the edge of the water in the large bay, perched on a reclaimed landfill, a permanent archery range was erected. Nextdoor, a spectacular temporary finals arena was built with capacity for more than 5600 people. It had a design that looked, from the outfield, almost like a classical piece of Japanese architecture.

It might have been the best Olympic finals field ever constructed – but would sadly never see a paying customer. Only a handful of teammates, coaches and press would ever sit in its acreage of seats. At full capacity, you could only imagine what a theatre it would have been.

Of course, no one could have predicted what would happen in 2020.

The Olympic Games were finally held in 2021 after an unprecedented postponement and with Japan still not recovered from the swirling pandemic that upended the entire world. For the first time in Olympic history, the Games were held behind closed doors, with the venues open to television cameras and journalists – but not an audience.

Such decisions remain controversial – but not as difficult as the decision to have them go ahead. The extraordinary protective system, staffed by countless volunteers and professionals, isolated Olympic visitors and (largely very successfully) prevented any further outbreaks. For a lot of the sporting contingent, getting Tokyo over and done with was simply an immense relief.

But in the reality of the arena, despite the protocols, despite the empty seats and despite the delay, the atmosphere was… Olympic.

A record five archery medals were awarded over a record eight days.

In the intense Japanese heat, An San took a record three of those, winning first mixed team, then team and, finally, individual gold. The unprecedented haul for a single archer at a single Games propelled her into joint-fourth in the all-time Olympic medal table and made her an overnight sensation in Korea.

Tokyo also brought a first-ever archery medal for Turkey as Mete Gazoz leapt in celebration after becoming Olympic Champion.

His reaction, seconds after loosing the last arrow of his final against Mauro Nespoli, was the perfect release after an intense competition, featuring some of the closest-fought battles in Olympic history, made all the more poignant by the delays and uncertainty of the previous year-and-a-half. (And seen, on screen, as the first Games to feature on-screen heartrate figures during shooting, visualising the immense pressure on the athletes’ shoulders.)

“We’ve waited 100 years for this,” said Turkish head coach Goktug Ergin after the final.

“After 2016, after Rio, I promised myself I would be Olympic Champion next time in Tokyo,” said Gazoz, a full-time professional archer since his early teens. “I worked really hard, I did all the things necessary to be here, to be on top of the podium, and I’m really happy to be able to win this medal.”

The future of Olympic archery is bright.

The competition will be held at Invalides in Paris in 2024 – right in the centre of the city – and World Archery has proposed compound’s inclusion at LA28. If the latter is approved, a brand-new chapter will begin.

Much has changed since archery returned to the programme of the Olympic Games in 1972.

Then, the format was geared towards the history of the sport, now it balances competitive results with spectator enjoyment. Then, archery was an outsider, now it is core to the Olympics. Then, the athletes were amateurs, now they are professionals.

But at least one thing remains.

“The Olympics is a dream,” said John Williams, who won the men’s event in 1972. “And I was able to fulfil that dream.”