The long road to archery’s Olympic return at Munich 1972

Modern archery is somewhat defined by the Olympic Games. It has guided and shaped the sport into what it is today.

Since 1972, when archery returned to the Olympic fold, it has become by far the most important event on the international calendar. Although only recurve archery is currently practised at the Games, its impact on the rules and popularity of the sport is wide-reaching, and there’s also a chance that more events could be added in the near future.

After the first modern Olympics were held in 1896, archery was included on the programme of the Games in 1900 in Paris, 1904 in St Louis, 1908 in London and then 1920 in Antwerp.

As a sport at that time, archery was coming to the end of an era as a fashionable pursuit for the social elite of Europe, still practised largely by aristocratic hobbyists. The Olympics themselves were very different from the event we know today, too. In 1900, the Games were merely the sports section of a huge international event called The World’s Fair, which was similar to our contemporary World Expos.

There were 13 associated archery competitions held during the dates of the event, with over 5000 archers taking part – all men.

To date, there’s not been official consensus as to which competitions were ‘Olympic’ and which were not, although the relevant Wikipedia page lists seven picked by unidentified Olympic scholars. The rounds shot, including the delightfully named Au Cordon Doré – ‘with golden cord’ – would not appear again, and while the tournaments were open to all comers, in practice almost all the archers who competed were French.

At the Olympic Games in St Louis in 1904, team events appeared for the first time. Again, while officially open to all, no foreign athletes competed and the event became the de facto US national championships.

In 1908, when the Olympics came to London for the first time, the country’s top female archer of the day was Alice Legh. She decided to skip the Olympic Games to prepare for the British national championships – which at the time, she apparently regarded as more prestigious.

Archery at those early editions of the Games may not have represented a multitude of nations, but the competitions in 1904 and 1908 were pioneering in terms of featuring women at all.

This was an era in which male Olympians often outnumbered the women at the Games by a factor of 20 to one. Not all sports were nearly as welcoming as archery. Some have theorised that archery was perceived as acceptable partly because women could compete while wearing a dress. It’s perhaps not the honourable reason – gender equality – we’d like to find, but it laid a pioneering foundation for so much of the sport’s history.

In 1920, the events were changed yet again. The Olympic competitions that year involved variations on what is called popinjay archery, which is shooting arrows to try and knock wooden birds from high poles. This was a form of the sport popular, then and now, mostly in Belgium. Only three nations were represented: Belgium, France and the Netherlands.

Local hero Hubert van Innis would win the last of his nine gold and silver medals to become, and remain, the most decorated archery Olympian of all time.

After that competition in Antwerp, Olympic arrows would not fly again for 52 years. The Games were becoming increasingly important, prestigious and professional – even if the events remained strictly for amateur participants. To be included at the Olympics, a sport needed a standardised set of rules for international competition. A constant rotation of rounds and limited foreign participants would no longer be accepted.

Many international sports federations were established in the early decades of the 20th century.

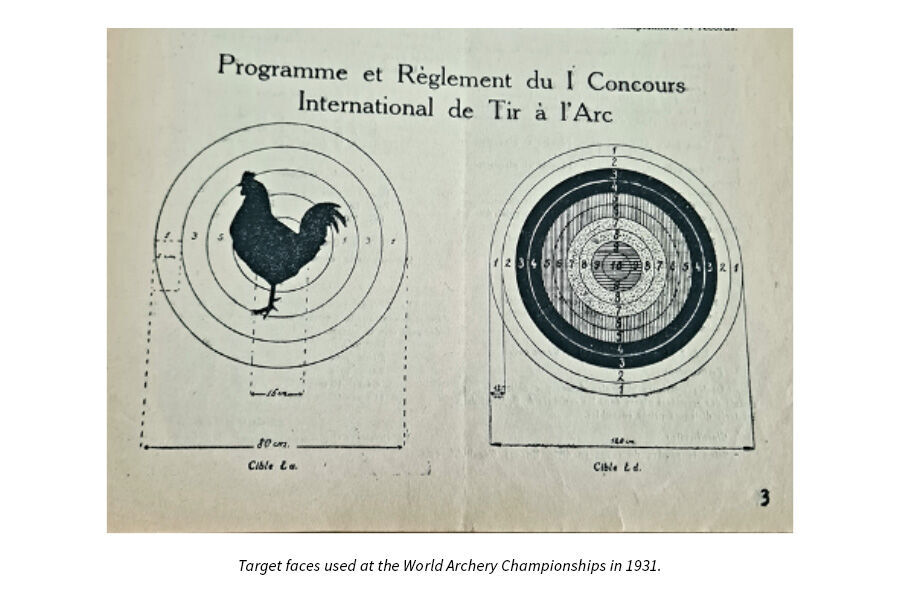

World Archery, then known as FITA, was founded in 1931 in Poland. Just seven countries were represented at the inaugural meeting: France, Czechoslovakia, Sweden, Poland, the United States, Hungary, and Italy. (More than 90 years later, World Archery’s membership consists of national federations in around 160 countries.)

Right from the start, one of the primary goals of FITA was to return the sport to the Olympic Games. The very first meeting outlined the specific purposes of the organisation:

- To foster international sporting relationships leading to participation in the Olympic Games.

- To organise international archery competitions.

- To underwrite the prizes for the competitions.

- To assure the observance of technical rules in the competitions.

- To confirm and endorse world championships and records.

A resolution was immediately passed, at that same meeting in 1931, to approach the International Olympic Committee and request archery be reintroduced to the Olympic programme. That request was quickly denied.

It was the first setback of many. It took years just to establish specific rounds and standardised targets – the first competition rules that stuck weren’t approved until congress in 1935 and introduced until 1936 – and minutes of meetings over the next few decades contain numerous wistful reports of approaches to Olympic committees, delegates and officials around the world.

None of them were successful in returning archery to the Games.

Progression was slow but by 1950 archery was recognised as an amateur sport by the International Olympic Committee. At the same time, FITA was recognised as an amateur federation.

In 1952, FITA’s first official Olympic archery rules were accepted by the International Olympic Committee in case archery was re-admitted to the fold. However, the more austere Olympics held after the Second World War were not keen on introducing new sports. Archery, for all its history and universality, apparently had not made its case.

The key figure behind archery’s eventual return to the Games is Inger Frith.

Born in 1909 in Denmark, she led a remarkable globetrotting life, including serving in the South African Air Force during the Second World War, before settling in the United Kingdom and taking up archery, eventually representing Great Britain internationally.

In 1955, she became a vice president of FITA and began her campaign of ferocious lobbying to return the sport to the Olympics.

By 1961, she had become the first female president of an international sports federation. In that era, not everyone even realised that Frith was a woman. According to a note in the Olympic Review: “she asks us very courteously to make it known that her feminine pride is slightly ‘hurt’ when she receives letters addressed to the president of the international archery federation referring to her as ‘Mr’.”

According to contemporaries, Frith had an autocratic character.

“She ruled archery with a rod of iron,” according to 1972 Olympian Lynne Evans. “But she is credited with not giving up and literally walking the corridors of the International Olympic Committee and demanding that archery be let in.”

Frith apparently had charm in abundance. Francesco Gnecchi-Ruscone, who would take over from Frith as president in the 1970s, candidly said:

“She had the great merit of making herself irresistible to Avery Brundage, who was then the president of the International Olympic Committee, until he agreed to let archery come on to the Olympic programme.”

Munich was chosen to host the 1972 Olympics in April 1966 at a session of the International Olympic Committee in Rome.

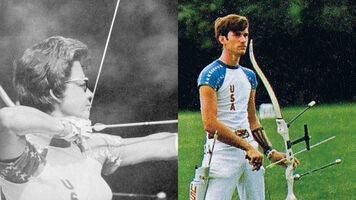

One year prior, Frith had received confirmation that the sport would be permitted its return. But it was at that session that the news that FITA had been waiting decades for was officially public. Archery would join the programme in Munich – and it would be one of only nine (out of 21) sports to feature a competition for women as well as for men.

Frith wrote to the secretary general of the International Olympic Committee following the decision.

“We are determined to make an unqualified success of the honour that has been given us in becoming part of the Olympic Games 1972,” read the letter.

After more than 50 years, a new chapter had begun.

Some photos courtesy Yoshi Komatsu and the International Olympic Committee.