The history of the English longbow: Crooked stick and goose wing

In the early centuries of the first millennia, Britain was occupied by the Romans, Atilla the Hun was rampaging across Eastern Europe and China was coming to the end of the Han dynasty. And someone was carefully placing prototypes of what we would now recognise as a longbow inside a ritually buried Saxon warship in Nydam Moor in Denmark.

The bows found there during an excavation in the mid-1800s were made of yew. Some savvy Iron Age bowyer had noticed that the wood had useful properties when shaped and bent.

Yew is naturally elastic – but that’s not really what makes a longbow. The crucial leap was using sapwood, the outer part of the tree, as the outer and rear part of the bow. The inner, ‘belly’, was made of the rounded inner heartwood, forming a D-shaped cross-section.

The inner heartwood resists compression. The outer sapwood performs better under tension, allowing it to bend and store an enormous amount of kinetic energy yet return to the same shape and state once shot.

Talking about the properties of wood might seem superfluous in the modern age. But, 1500 years ago, this was a gigantic leap forward in materials science.

Many older yew bows have been found by archaeologists but the Nydam Moor bows were the first in Europe that can be placed in a definitively military context. At this stage, the wooden bow had changed from a hunting tool to a weapon.

What is strange is that for 1000s of years, in terms of technology, the longbow had already been rendered obsolete.

Around 4000 years ago, in Asia, ancient bowyers had begun to construct composite bows made of multiple layers of wood, animal horn, sinew and glue. European bows were universally shaped from single pieces of wood.

Across the world, humans had started to domesticate horses for transport, hunting and eventually war. The required length of an effective single-piece wooden bow – usually at least as tall as the person using it – makes it very difficult to use from horseback. The composite bows of Asia were shorter but had higher power and led to mounted archers.

Composite bows, though, are much more expensive and complicated to construct. Some took years to make and needed a huge range of skills and materials. A simple longbow can be constructed in a few hours from locally available wood and with relatively limited tools.

That’s not to say that the English bowyers of old were not talented nor skilled in creating quality equipment. They sourced the very best quality yew wood because it works as a natural ‘laminate’, gaining some of the efficiencies of a multi-material bow.

And while contemporary composite bows were more sensitive to environmental changes, longbows that were well-protected with wax and tallow would continue working under more difficult conditions.

As a weapon suitable for large-scale deployment, it was the simpler and far more cost-effective tool. It was reliable, powerful and mass-produced in vast numbers.

It was also a weapon that would change the landscape of Europe during its halcyon days in the early 1000s.

The Battle of Hastings in 1066, which began the Norman conquest of Britain, involved massed ranks of archers who played a key role in the victory. Powerful longbows, with horn nocks and heavyweight, iron-tipped, goose-feather-fletched arrows became a mainstay of the armouries of Britain over the next few centuries.

Men were trained from youth to pull them. Statutes exist requiring weekly practice and many British town centres have areas still named ‘butts’ after the targets that once stood on the land.

A document from 1338 detailing an order for King Edward III’s armourer asks for 1000 bows, 4000 bowstrings and almost 100,000 arrows. And it was just one of the dozens of similar requests.

By this time, archers formed half of the rank and file soldiers available for the many conflicts of the era, with a thriving artisan supply chain of bowyers and fletchers required to support them.

Just over 600 years ago, on the morning of 25 October 1415, a small band of English archers commanded by Henry V won a military victory over French forces in one of the many conflicts of the Hundred Years War. It has been known as the Battle of Agincourt and has been celebrated ever since in British history as the archetypal underdog story.

The legend was famously retold by Shakespeare in Henry V and that is where we get the phrase ‘band of brothers’.

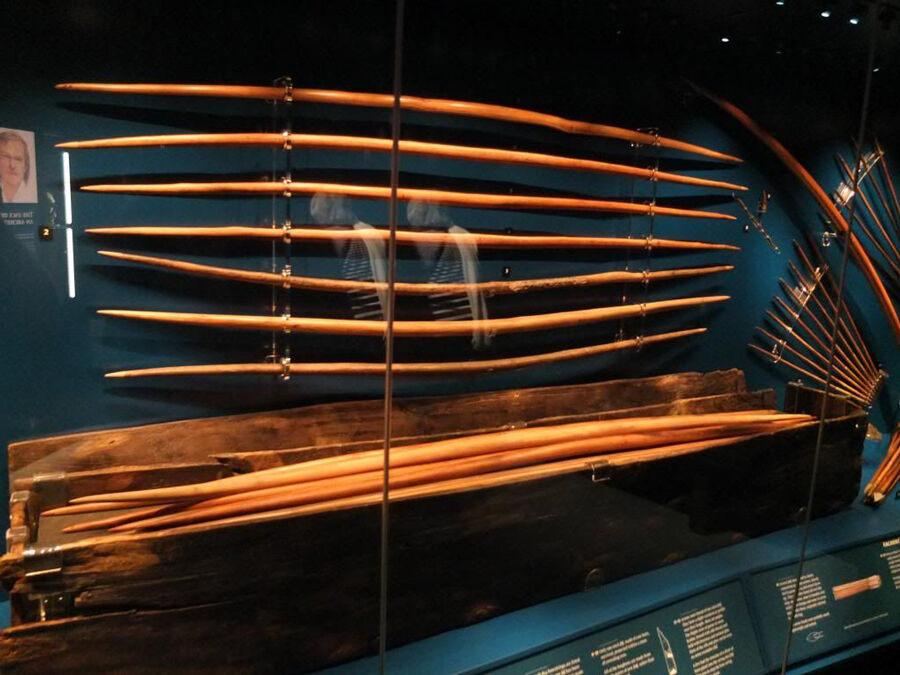

Despite their military fame, no longbows from this period have survived to the present day. Much of what we know about their history is gleaned from the haul found on the Tudor warship Mary Rose, which sank suddenly off the South Coast of England in July 1545. It was raised from the seabed in the 1980s in an amazing feat of maritime archaeology.

The reigning monarch at the time of the Mary Rose’s demise was Henry VIII, who was a keen longbow archer himself. He enthusiastically encouraged the military use of the longbow even as he pursued the development of gunpowder artillery.

Over 150 longbows, averaging over six feet in length, and many 1000s of arrows were recovered from the wreck of the Mary Rose.

While the arrows were relatively standardised, the bows came in multiple lengths and draw-weights, with few niceties about their finish. There were no indications of any binding around the grip, with just a few small marks on the upper limb to indicate who was shooting what.

Enough bows were found to test a couple to destruction.

A survey of the bow weights ranged from 100 pounds up to an eye-watering 180 pounds – around three times what archers might use today. Bows this heavy would require many years of hard training to learn how to use and would change the shape of the body.

Many 1000s of human bones were found with the ship and archaeologists have now tentatively identified some of the archers on board by a medical condition called os acromiale. It is a mis-formation of the shoulder blades, thought to be brought on by pulling very heavy bows since childhood.

Every longbow on the Mary Rose was found to be made with high-quality yew. For such a fabled ‘English’ technology, almost all the yew had come from continental Europe.

Henry VIII sent agents to Italy, Austria and Poland to find the finest, tallest, close-grained yew for export back to England. Documents have been found recording orders for 40,000 bow staves at a time, shipped directly to well-paid expert bowyers.

Longbows were fast and accurate – but required years of training and skill. Warfare was seasonal in this era and maintaining a standing army of practising archers was too difficult.

By the end of the Tudor era, with gunpowder weapons spreading across the world, the longbow would start to leave the armouries of England.

Its role as a frontline military weapon was ending. The transition into a tool for sport and leisure that has continued to the present day.

The first-known target archery competition took places in Finsbury, England in 1583 and had 3000 participants. Longbow shooting was a fashionable pursuit in the late 18th century, seen even then as a nostalgic, romantic activity.

But there is one final military tale to tell.

In the Second World War, a bagpipe-playing Lieutenant Colonel called ‘Mad’ Jack Churchill is said to have wielded his longbow during the retreat to Dunkirk in May 1940.

The story fits a narrative. Churchill’s escapade is part of the uniquely English take on the wider mythology where the bow becomes the symbolic protector of the nation. As an ancient ballad goes:

“England were but a fling, but for the crooked stick and the grey goose wing.”

Expert bowyers continue to make longbows in England today using the same techniques that rose to prominence many 100s of years ago.

World Archery’s longbow division, which is currently used at the World Archery 3D Championships, includes the typically English longbow as well as other traditional pieces of equipment from around the world.

Thanks to Hugh Soar and Evelyn Tribble for their assistance.