Archery history: Tribal use of the bow and arrow through the modern day

While it is difficult to determine the exact moment archery was born - some claim the discipline dates back almost 70,000 years - the trajectory of archery’s early growth, migrating out of ancestral Africa to the rest of the world, is clear.

As mankind’s first piece of advanced technology, which has been refined and improved countless times over millennia, the bow and arrow offered practitioners an almost insurmountable advantage across a variety of disciplines.

In Europe, a tradition of wooden self-bows and longbows developed, while in Asia, the shorter composite bow and mounted archery held sway for 1000s of years.

Since its origins, archery has moved in every direction. And that has resulted in an incredibly diverse set of practises, traditions and cultural implications for the ubiquitous tools of the bow and arrow.

ACROSS THE LAND BRIDGE

It is generally understood that humans first entered North America from Asia across the Bering Strait, via Alaska, in several waves, beginning around 20,000 years ago. It’s pretty certain that archery migrated then, too, because when European contact started in the Middle Ages, the bow was universal throughout North America.

The tradition in the Arctic was to use self-bows, which while theoretically constructed from a single piece of wood the resource was often so hard to find that they were often constructed from multiple pieces of wood and horn held together with complex tangles of sinew.

In the more southern parts of North America, shorter and more complex sinew-backed bows made from local woods like hickory, ash, osage and black locust were developed, of both recurve and decurve designs.

After the horse was reintroduced to North America in the 1500s, a tradition of mounted archery developed – and this became a totemic symbol of the continent until firearms became widespread.

In Native American tradition, the bow and arrow became an embodiment of power and magic, a power granted through the spirit world. Bow- and arrow-making became a specialist skill, just like in medieval England.

Around 1000 years ago, the technology resulted in the triumph of the bison-hunting peoples of the plains, which transformed every native society in North America.

Much of what we know about Native American archery tradition and skill comes from Ishi, the last surviving member of the massacred Yahi India tribe, who came out of hiding in California in 1911 at the age of 50.

Ishi’s extraordinary archery skills had some distinctly Asiatic features. His bow release was a variant of the “Mongolian release”, using the thumb to draw the string, but without a thumb ring, and on release he relaxed his bow hand to let the bow rotate in the hand – which is what Japanese kyudo archers still practise.

His techniques for flintknapping, bowmaking, and bowhunting are still studied today.

HEADING SOUTH

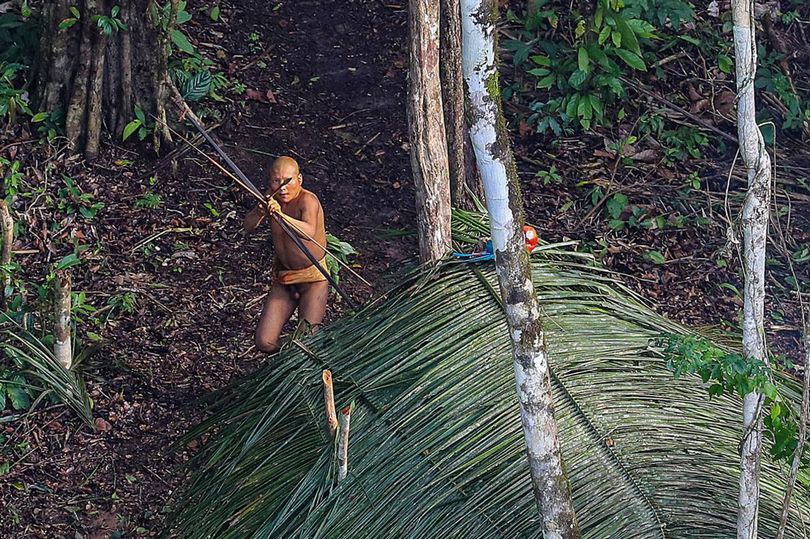

Traditional archery among aboriginal people of the Americas is still intact today among indigenous groups in tropical South America, where sheer inaccessibility has prevented foreign contact until relatively recently.

Now sometimes referred to as “uncontacted people”, these communities are now mostly found in densely forested areas of Amazonia. Many of these groups live within protected areas that allow them to continue to follow a traditional lifestyle, and the use of the bow remains routine.

Most indigenous forest peoples use simple self-bows constructed of local materials such as palmwood, beechwood and letterwood. The extremely long arrows commonly used – up to 2.5 metres – are tipped with bamboo or wooden heads, depending on their use, and are too long to make quivers practical. So instead, they are usually carried in the archer’s hand.

The arrows are so long that they can be used as a kind of lance when there is no time to draw a bow. Some tribal people still use poisoned arrowheads, which are usually carried separately in a special container.

While indigenous people in Amazonia still use the bow, from the minimal studies that have been made it is nothing more than a tool – one among many that must be used for hunting and survival.

ACROSS THE OCEAN

Culturally and historically, Amazonian peoples resemble island nations, drawing on shared identity and developing distinct traditions. The technology of archery is mappable worldwide but not always significant.

Ancient Indonesian artworks frequently depict archers, but it is not considered a key part of the history of the continent.

However, in Yogyakarta, on the island of Java, a form of archery called jemparingan is still practised. It involves shooting seated, aiming at a white target just 3.5cm wide set 30 metres away.

Jemparingan, like other archery traditions, is considered a form of spiritual development rather than a tool for survival.

West of Yogyakarta, across the Indian Ocean, lies the Andaman Islands, in the Bay of Bengal between India and Burma. These are inhabited by the Andamanese people. Two tribes of this group, the Jarawa and the Sentinelese, are notorious as the fiercest and most independent of all indigenous peoples around the world – and some of the most skilled archers.

Notably, the Sentinelese, who inhabit the tiny, 60-square–kilometre North Sentinel Island, might be the most hostile sovereign nation on Earth. While the islands are technically ruled by India, in practice, the government leaves the island alone to manage its own affairs.

Almost every attempt at contact in the past century has been met with a relentless hail of arrows. Most of the handful of photographs ever taken of the islanders show bows pointed directly at the camera.

Archery has, ultimately, protected this last enclave from total destruction. Over 90% of Andamanese islanders died out in the 18th century after encountering foreigners and suffering from subsequent disease.

Some facts about their archery traditions have appeared from the tiny handful of peaceful contacts in the past century. The Sentinelese use a highly efficient flatbow with paddle-shaped limbs, well over a metre long and with immensely long cane arrows, fire-hardened and tipped by cold-smithed scavenged metal.

These arrows are used for hunting turtles and wild pigs, as well as defence. In 2018, an American missionary approached the islands illegally, and one of these metal-tipped arrows struck the Bible he was holding.

A subsequent solo visit saw him shot again. He later died. It’s an incident that made headlines around the world.

Archery is now, primarily, a sport. Its widespread use in warfare has long-since become obsolete and, in its original form, is often seen as part of history. In countries as far apart as England and Bhutan, the bow and arrow have become a symbolic protector of the nation – and a reminder of past conflicts.

In a very few isolated corners of the world, those traditions remain very real.