50 years since archery crowned its first modern Olympic Champions

Today marks 50 years since the conclusion of the archery competitions at Munich 1972, the Olympics in which the sport made its return to the programme of the Games after a 52-year hiatus.

In that era, the USA was the dominant nation in archery.

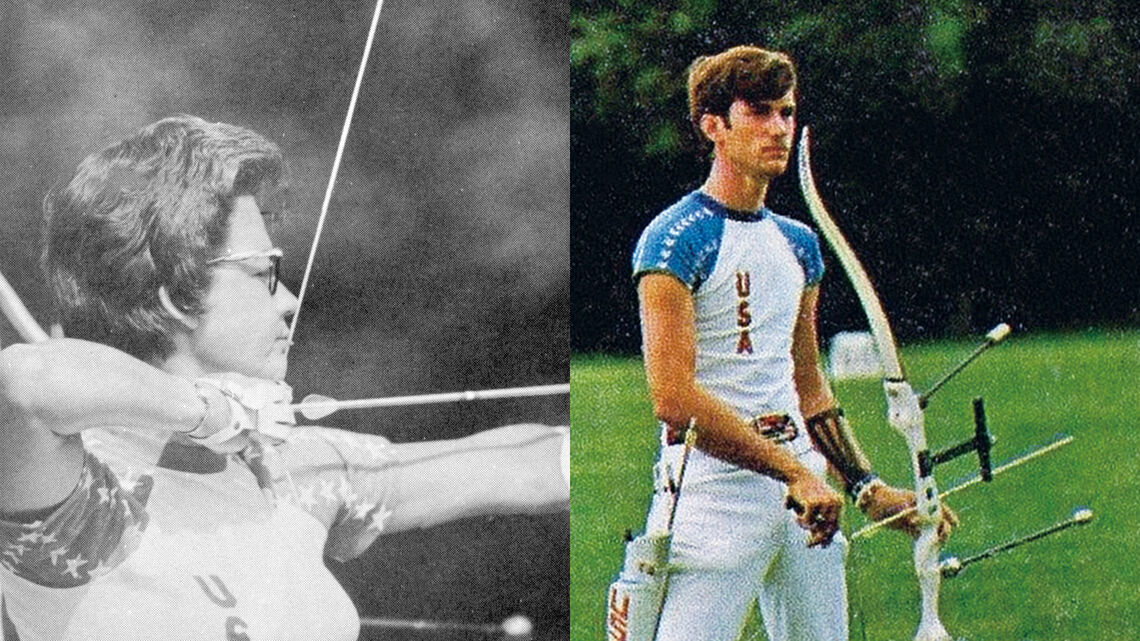

The favourite in the men’s competition, arriving as the reigning world champion, was an 18-year-old army private from Pennsylvania called John Williams. Speaking to World Archery from his home in 2021, he relayed his extraordinary story.

“After the announcement in 1966 that archery would be included in the Olympic Games, I went from the junior division to the adult division right away and started shooting against the adjust at age 13,” he said.

“I shot my first world championships in 1969 in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania at the age of 15. Two years later in England, I was world champion. So everything was rolling. I was in the right place at the right time. I was peaking repeatedly at the tournaments that I needed to peak at.”

It was a different era, with different training methods – but the commitment of an elite archer is recognisable through the ages.

“I stayed awake a lot of nights staring at the gold on the target on my bedroom wall,” said Williams. “I guess you can call that mental training. But it’s nothing to what they do today.”

Hoyt had supplied the US team with bows for Munich, but Williams was forced to write a token cheque for a dollar so he didn’t fall foul of the strict rules about amateurism that were in place for the Games. Athletes were forbidden to receive money or gifts at the time – with an Olympic ban the penalty for breaking the code.

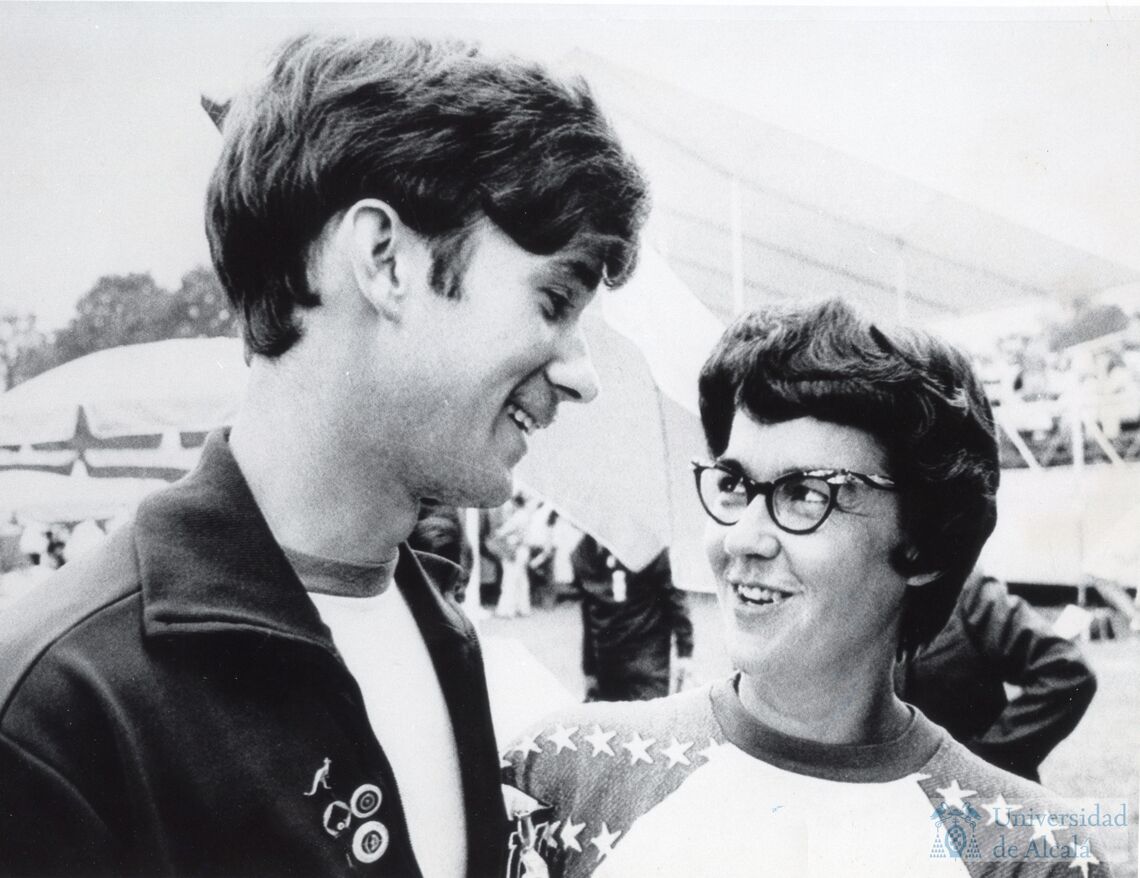

Coached by his father, Williams took first place in the US team trials.

“I was about as excited as I could be over anything. I mean, this was the Olympics. I wasn’t just shooting against kids, or the people in the United States anymore,” he said. “It was the whole world.”

The USA delegation arrived in Munich a few days before the opening ceremony and Williams began practising hard, shooting 250 to 300 arrows every day: “Things were going along pretty smoothly right up until the incident, which actually happened the day before we were supposed to start shooting.”

John was referring to what is now known as the ‘Munich massacre’, an attack that saw 11 Israeli athletes kidnapped in the Olympic village, held hostage and then murdered. Williams had a front-row seat.

“It’s one which I relive every four years because the picture that they broadcast every four years of the guy standing on the balcony, I saw that through my binoculars,” he recalled, not attempting to hide his emotion. “The American [athlete] building was only about 100 yards from where everything was happening.”

The atmosphere of the Olympics changed instantly.

“It went from excitement and enjoyment, every partying at the discotheque, to… everybody was afraid,” said Williams. “It went from really, really lax security, I have to say, to armed guards walking the perimeter of the fence and tanks in the underground parking lot.”

“I just had to hope and pray that things were going to move forward and I had to be prepared for that eventuality, which we were all hoping for,” he continued.

Competition at the Olympics was suspended for 34 hours. At one point, the last four days of the schedule, which included archery, were nearly cancelled. The then-president of the International Olympic Committee, Avery Brundage, controversially insisted that the Games continue – and the decision was endorsed by the Israeli government and the chief of Israel’s team in Munich.

During the suspension, the archers’ training facilities had been closed. US coach Clarence “Bud” Fowkes scrounged around the village for newspapers to stuff into cardboard boxes, creating improvised target bales so that athletes could practice in their rooms.

With competition on the horizon, the enforced day off may have helped Williams’ chances.

“I needed a day off. I’d been practising so hard,” he said. “I was having some timing issues. I was having some issues getting used to my new bow and that day probably let everything soak in that I’d been doing, and the rest was muscle memory.”

A memorial ceremony for the 11 athletes who lost their lives was held in the Olympic stadium on 6 September 1972.

“And then everything was supposed to go back to normal,” said John. “We got up the next day and got bussed out to the field and the whistles blew.”

On 7 September 1972, with his mother and father sitting in the stands, Williams opened with a score of 52 out of a possible 60 points for his first six arrows at 90 metres. It put him in the lead – when he was normally a slow starter.

“I wasn’t used to being in that position,” said John. “It scared me to death.”

“There was no way to avoid looking at the leaderboard. It was 60 feet wide and 30 feet high and I knew where I was,” he added. “I went back to my dad and I said, ‘what do I do now?’ Because I was always used to chasing somebody. And my dad said, ‘you shoot like you’re 20 points behind!’”

Williams never left the front, despite shooting a miss at 50 metres.

“During the first FITA, I hit the 50 and I had one of those arrows that everybody has once in a while. The ones that just kind of you… you’d love to get your fingers back on the string but you can’t,” he said.

On the fourth and last day of the men’s competition on 10 September, just before the last three arrows, Victor Sidoruk – the athlete sitting in seventh and representing the Soviet Union – walked over to Williams, gave him a bear hug and a kiss on the cheek. The US archer was 47 points in front.

“I still had three arrows in my quiver. I really think I just zoned out… okay, here’s one arrow. Here’s the second arrow. And here’s the third arrow,” said John.

It was done. Over two days, John had scored 2528 points, set a new world record and become the first men’s Olympic Champion of the modern era. Gunnar Jervil of Sweden came second with 2481 points and Kyösti Laasonen of Finland third on 2467.

(Laasonen would compete in three more Games, alongside his brother Kauko in 1976 – one of several pairs of siblings to compete in the archery events in the years since.)

The women’s competition was also won by an archer from the US – Doreen Wilber. In contrast to Williams, a youthful soldier, Wilber was a 42-year-old housewife from Kansas. She was a top American archer for a decade, breaking multiple records and becoming the first woman to shoot more than 1200 points for the FITA round in international competition.

In Munich, she sat fourth after the first 144 arrows, behind Irena Szydłowska of Poland and Emma Gaptchenko of the Soviet Union. However, her second half of 1226 points was enough to vault Wilber into first as Szydłowska and Gaptchenko slid down into second and third. Doreen’s total of 2424 points was also a new world record.

Hailing from rural Iowa, Wilber allegedly only began archery after her husband, a mechanic, received a bow and arrows instead of an unpaid bill. Despite a lack of formal coaching, she dominated the 1960s in domestic competition and abroad. She’s still revered today as a model competitor – disciplined and generous in equal measure.

When she returned from the Olympics, the state governor greeted her at the airport and a caravan of cars escorted her to her hometown of Jefferson a welcome party of 2000 people.

Wilber died in 2008 at the age of 78 but she remains the oldest woman to win an Olympic archery medal in the modern era. Jefferson has erected a life-sized bronze statue – of Doreen at full draw – in her memory.

She continued to shoot internationally for a few more years but never returned to the Games.

Szydłowska represented Poland again at the Olympics four years later in 1976, finishing 20th, while Gaptchenko would win medals with the Soviet teams at world and continental championships in the following years, and went on to a well-remembered career as a coach and a judge.

The Olympic gold medal opened many doors for Williams and he became one of the first professional archers of the era, coaching around the world, giving exhibitions, appearing on television shows and working with Japanese equipment manufacturer Yamaha for many years.

But the strict rules about amateurism in the 1970s meant he couldn’t fully reap the financial benefits of his Olympic success and remain an Olympic athlete, alongside the extraordinary talent that was rapidly rising through the national ranks.

“If it was the way it is today, I’d have probably shot for another 20 years. It would have been difficult against Darrell [Pace]. It would have been difficult against Rick [McKinney]. But we made a great threesome. We would have made a very powerful men’s team,” said Williams.

Williams went on to coach Luann Ryon to women’s gold at the next Olympics in Montreal and was also the home team’s coach at Los Angeles 1984. (The USA boycotted the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow.)

He donated his Olympic gold medal, along with the bow and arrows he used to win in Munich, to the Archery Hall of Fame in Springfield, Missouri.

The archery competitions in 1972 closed out a troubled Olympics.

For the sport, the Games were also pivotal. After a 52-year hiatus, archery had returned to the global stage and the Olympic programme.

One of archery’s two first modern Olympic Champions, Williams relished every moment of his win.

“To me, the pomp and circumstance of the Olympic Games, combined with that full FITA, everybody on the field in white – it was a pretty spectacular sight,” he said in 2021.

“I remember it like it was yesterday.”

“I remember taking that big step onto the podium,” he continued. “And I still can’t watch the flag go up at a baseball game without crying.”