Archery history: Horseback archers of the East, Orient and ancient world

Around 4000 years ago, an entirely new and highly specialised tradition of bow-making was developed. Rather than shaping tall bows from a single piece of long wood, ancient bowyers began constructing more compact designs made out of composite layers of wood, animal horn, sinew and glue.

The shift in styles aligned with a rise in the use of horses in the ancient world.

Mounted tribes were capable of migrating across entire continents and the wooden bow, which needed to be almost as tall as the person using it to be effective, was no longer a viable tool. Composite bows were shorter and more powerful – and, critically, could be used on horseback.

It’s as challenging as it sounds – both then and now. Using a bow while sitting on a horse requires the rider to let go of the reins with both hands, requiring excellent equestrian skills to remain in sync with the animal as well as archery ability to accurately release an arrow.

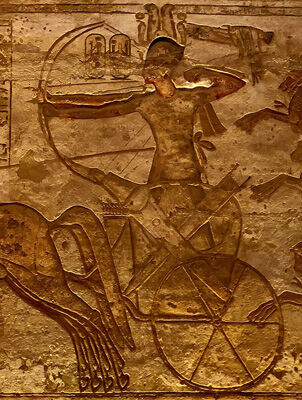

The relationship between archery and horses can be traced back at least to the ancient Egyptians.

In the glory days of the New Kingdom, around 1300 BC, shooting from a chariot was a skill so desirable that even pharaohs such as Rameses II were depicted practising it. In total, 20 composite bows were found in the tomb of Tutankhamen, many inscribed with his name.

Perhaps the most legendary early mounted archers were the Scythians, a collection of aggressive nomad tribes who struck fear up and down the Silk Road around the 7th century BC, and whose archery skills were lauded across antiquity.

As historian Jacob Bronowski said in the 1970s:

The Scythians were a terror that swept over countries that did not know the technique of riding. The Greeks when they saw the Scythian riders believed the horse and the rider to be one, that is how they invented the legend of the centaur… We cannot hope to recapture today the terror that the mounted horse struck into the Middle East and Europe when it first appeared.

Already masters of horsemanship, the Scythians developed lighter archery equipment to increase their speed. Additionally, they opted to use a bowcase and quiver called a gorytos, attached to a rider’s hip and easily accessible. At least one surviving example has been proved to be made from human skin. By this time, the composite bow had been radically improved, with the ears and grips strengthened with bone.

(The Scythians are also credited with inventing the saddle, an almost equally important invention to human history as the bow.)

Across the ancient world, empires rose and fell. In turn, the Assyrians, the Persians and the Etruscan armies all employed horseback archers, each celebrated in their time for their nobility and expertise.

The Persians, founders of the first true world empire, were said by Herodotus to train their sons from the age of five to 20 in four things only: “riding, swordsmanship, archery, and truth-telling”.

Large armies rarely relied solely on skirmishing horse archers, but there are many examples of victories in which horse archers played a leading part. Alexander the Great used mounted archers recruited among the Scythians and Dahae during the Greek invasion of India.

Archery was not a usual feature of the Roman military (as they belatedly realised), but the Romans, scarred from battles with mounted archers, later made use of foreign levies, with regiments of equites sagittarii acting as Rome's horse archers in combat.

The Parthians, an ancient Iranian people who built their empire around 50 AD, are credited with inventing the military tactic known as the “Parthian shot” – turning and shooting an arrow from a horse while galloping away from the enemy – a technique that rapidly spread across the ancient world.

However, not all mounted archers were fast and light. Heavyweight horse archers, such as those in the Byzantine and Turkish armies, gradually formed into disciplined units, and shot as volleys rather than as lightweight individual attackers.

The most extraordinary triumph of mounted archery came from 12th-century Mongolian leader Genghis Khan. Over 50 years or so, this illiterate horseman and his handful of troops built the largest contiguous empire in history, defeating far more advanced armies with a well-trained army of disciplined archers on horseback.

Unlike his enemies, Khan realised the immense military potential of mounted archers and their ability to overcome greater numbers.

His ranks included both heavy and light horse archers, with each soldier carrying up to 70 arrows with different points to cover a variety of battle situations, including armour-piercing steel points, grenades and incendiaries. These arrows were carried in specially divided quivers.

Khan saw that the massed arrow volley was a tremendous psychological weapon. His archers would ride in tight ranks and unleash volleys at targets selected and marked out by whistling arrows. This terrifying power led to Mongol victories in the 1200s over far larger armies in China, India, Russia and Eastern Europe.

Khan eventually conquered all of China, and his descendants came close to conquering the known world, by which time mounted archers were becoming almost mythically powerful.

Horseback archery, in turn, became part of the rising Chinese culture in the middle of the last millennium, and archery and equestrianism became essential skills for the elite and the bureaucracy in the region right up until the 20th century.

Worldwide, horseback archers were eventually rendered obsolete by the full development of firearms around 1500 AD, although many cavalry forces in the East did not replace the bow with the gun until shorter, more practical firearms had replaced the musket centuries later.

The last major global battle with mounted archers, in 1758, involved Chinese mounted archery forces against Mongolian forces armed with muskets. The archery forces, using traditional manchu bows, won the day.

There are long traditions of horseback archery in China, Korea and Japan, but only one is still fully flowering today. Yabusame, a ritual display of mounted archery, is a subset of the traditional Japanese martial art. This style of archery has its origins at the beginning of the Kamakura period in the 13th century and was developed as a military exercise to train the famous samurai class of Japanese warriors.

Unlike almost all other mounted archers, yabusame practitioners use a full-length bow: the offset yumi bow used in kyudo, which dates back two millennia. The shorter lower limb of the yumi was originally designed so that it could be used on horseback, although the sheer length of the bow makes it difficult to control and shoot.

A mounted yabusame archer, controlling a galloping horse with his knees, shoots blunt arrows successively at three wooden targets along a 225-metre long track. The sheer difficulty of doing so was designed to develop character and discipline among the samurai class. Two major schools of yabusame exist to this day, and one of them featured in the film Seven Samurai (1954).

Yabusame is still publicly practised in Japan today as a colourful, gleaming display of cultural history. Similar customs are kept alive today around the world – and there is even an annual world championship for horseback archery, celebrating a tradition that literally transformed the world.

A European Championships, held in Poland at the end of 2019, attracted 42 competitors from 13 countries. They competed in Hungarian (designed to replicate attack and retreat in battle), Korean (replicating hunting) and Polish (cross-country) disciplines.

There are two main strands of horseback archery today. One is the research, revival and maintenance of the traditional skill and the other is its development as a sport.

The International Horseback Archery Alliance, founded in 2013, is an organisation devoted to encouraging the standardisation of rules and scoring systems for horseback archery competitions around the world.