The quest for Olympic archery’s holy grail – the back-to-back individual champion

They were tears of victory, but not of joy.

Ki Bo Bae arrived at her press conference in mourning, eager to apologise for the gold medal that adorned her neck. The glory of her accomplishment couldn’t redeem the manner in which she achieved it.

“Koreans do not shoot eights,” she said, refusing to celebrate the arrow that won her the London 2012 Olympic Games.

A perfectionist even by Korea’s ferociously competitive standards, Ki Bo Bae’s performance was a relative blunder when viewed within the prism of her country’s staggering archery legacy.

“I had heard a couple of people say I was lucky, and it made me emotional,” she explained recently. Even after guiding Korea to its eighth consecutive team gold just days earlier, she still felt compelled to prove herself.

Accusations of luck may have been overly harsh, but they served to underscore the narrative that has long followed Korea's archery elite.

Scoring that eight in the one-arrow shoot-off was enough to fend off Mexico’s Aida Roman for the Olympic gold at London. But would Ki Bo Bae have been as fortunate had she been vying for a spot on the Korean national team?

“Some people say it’s more difficult to make the national team than to win a gold medal in the Olympics,” said Park Sung-Hyun, widely considered the greatest Olympic archer of the 21st century. “Korea owes its current status to such a process. I think this process is one of the success factors that delivers Olympic medals.”

It’s hard to find evidence to the contrary. By any measure of accomplishment, whether individual statistics or overall team success, the Korean women are an undeniable juggernaut.

No other country has won the gold medal since the women’s team event was introduced at the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul.

Archers from Korea hold every outdoor world record in the recurve women’s category – the Olympic discipline – and they have collected eight of the past nine individual Olympic gold medals since 1984, making them perhaps the greatest Olympic team (across all sports) of all time.

Yet while the country being represented on the podium is a reliable constant, there are relatively few who have won that coveted title – when compared with a seemingly endless reservoir of talented athletes.

Collecting an Olympic gold medal might secure Korean athletes a monthly stipend for life, but it guarantees little else when it comes to archery. And for all the Korean women have collectively accomplished, no single individual archer has yet risen above the rest – and managed to successfully win and defend a title.

“Winning a medal in the Olympics is an act of God,” said Yang Changhoon, who was coach of the Korean women’s team at Rio 2016 and has been part of many successful squads at the Games.

“While experience matters, discovering new faces doesn’t count any less. We cull only the top-ranked athletes with excellent records only through competition for the national team, regardless of experience and age.”

Much has been made of Korea’s unconventional methods of ‘fear training’ – handling snakes, staring at bodies in crematoriums and walking through haunted houses, to name a (largely mystically) rumoured few – but the most formidable obstacle standing between an archer and the Korean national team might just be the archers themselves.

Korea never relies on a single archer to win the Olympic gold, instead placing its faith in the training and selection structures in place to develop a pool of capable archers – and, of course, an abundance of funding and resources to elevate its programme beyond those of other countries.

There are more than 100 full-time professional athletes in Korea. (A couple of years ago, worldarchery.org catalogued the teams spread across the country.)

The work is not, usually, a path to riches but there is funding to support a structure where archery is the focus of life – and many more archers can train with the express goal of earning Olympic glory, rather than the more normal system where only a select few are given national backing.

“Archery has many variables,” said Yang. “We joke that if someone hasn’t been able to compete in the Olympics representing Korea, they can join a national team and make it by going abroad.”

Survival is victory. Where Olympic qualifiers from other countries might enjoy more job security, relying on pedigree to maintain their standing, Korea pays little mind to reputation, opting for a more egalitarian approach, regardless of hurt feelings.

With the recurve standard creeping higher every year, it’s no wonder that Korea has been so successful. If an archer can overcome all of these barriers to reach the Olympics, returning home with a medal is almost a formality.

“I have competed in many international competitions as a member of the national team over the past 10 years, but no other national teams have had their members changed as often as the Korean team,” said Ki Bo Bae, who – for example – was left off the Korean roster for the 2017 Hyundai World Archery Championships just one year after finishing third at the Olympics in Rio.

That simple omission is just one example of Korea’s impartial approach to winning. Another is Kim Woojin, who was the reigning World Archery Champion during London 2012 and watched the event from home.

“Sometimes, athletes with rich experience fail to make the national team,” Yang acknowledged. “In those cases, I am regretful as a coach and even feel concerned because the team misses important assets. At the same time, we look forward to new faces. It’s up to the coaches to teach and grow such athletes.”

Ki Bo Bae came very close to defending her Olympic title from 2012 in 2016.

The only member of the women’s team in Rio with previous experience at the Games, she guided Korea to that eighth consecutive team gold and won individual bronze, falling to the largely unheralded Chang Hye Jin in the semis – who stepped out of the defending champion’s shadow to protect her country’s legacy.

“People often say ignorance is the best medicine,” Chang said of her victory over top-seeded Ki. “The pressure an athlete faces influences their performance in that competition. I was able to focus on the competition itself, rather than its outcome, and enjoy the competition because I was unaware of the pressure involved in the situation.”

That lack of previous Olympic experience doesn’t appear to be an obstacle for archers at the Games. If anything, an absence of exposure appears to be an asset.

Korea expects to win gold every time its archers step to the shooting line. The only variable in question is which newcomer it will be. Of the eight Korean women who have claimed individual gold since 1984, all eight have won at their first Olympics.

“I have rarely seen an athlete maintain their performance due to the sense of emptiness that follows the accomplishment of their goals,” Chang said. “The main gateway lies at the national competition, and you have to deal with those younger ones who are pushing hard against you.”

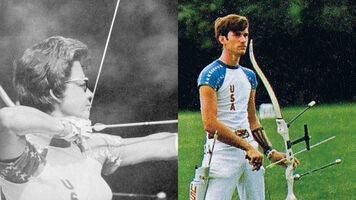

Since 1972 when archery became a permanent fixture on the modern Olympic programme, one archer – Darrell Pace – has won two champion titles, first in 1976 and then in 1984. (He also didn’t compete at Moscow 1980 due to the USA boycott.)

Two archers have come closer than Ki Bo Bae to defending the individual Olympic title.

Archery’s most decorated Olympian Kim Soo-Nyung won gold at Seoul 1988 and returned at Barcelona 1992 to take silver, surrendering the top spot to compatriot Cho Youn-Jeong. (Eight years later, she climbed the podium again at Sydney 2000, finishing third.)

And then Park Sung-Hyun, who had won in 2004, fell to China’s Zhang Juan Juan in the final of Beijing 2008. Zhang remains the only non-Korean recurve women’s Olympic Champion since Ketevan Losaberidze in 1984.

The weight of the moment – and the opportunity to repeat – is seemingly debilitating. Heading into Bejing, Park was the undisputed favourite and barely tested on route to her final obstacle. But Zhang, who had already defeated the other two Korean archers in the draw, delivered the upset to single-handedly extinguish a 24-year-old Korean stranglehold on the Olympic title.

Reflecting on her defeat, Park said she “was maybe too greedy”.

“It’s true that I felt more stress than at my first Olympics,” she explained, recently. “The disappointment was as great as the expectation. The Olympics are bigger than any other event. I tried to deal with the situation wisely, but I failed to focus on the competition.”

“I ended up not being careful enough with my actions. But I trained my hardest, and I have no regrets.”

The pursuit of a repeat individual champion will continue for the Korean women at next summer’s delayed Olympic Games in Tokyo – if Chang Hye Jin makes the team. She already received a lifeline in the postponement as she had been eliminated from the selection process.

The Korean Archery Association, following normal procedure, wiped the slate clean and restarted trials for the new year, Olympics or not.

In Tokyo, whichever athletes are selected to represent archery’s most successful nation at the Games will attempt to improve on the record-setting performance in Rio, where Korea swept all four available gold medals for the first time in history. There will be a fifth available gold in Tokyo – in the mixed team event, making its Olympic debut.

The Korean recurve women will also attempt to win a ninth consecutive title in the team competition. And it is the team, we are always told, that is the Korean priority.

Whether Chang can revive her Olympic bid and make history of her own remains to be seen. The road is long and the opportunity is singular. She has one title already secured, an exceptional five-year gap between these two Games, and little room for error at the most competitive of all international competitions.

“It’s what the female Korean archers must accomplish,” said Park.

If the Olympic gold medal is the greatest title in recurve archery, back-to-back Olympic gold medals is the holy grail. Three have come close – two very close – but all fell short.

The quest continues.