Shillong Teer, an ancient archery tradition in northeastern India

Archery is deeply rooted in many cultures around the world – and India is no exception.

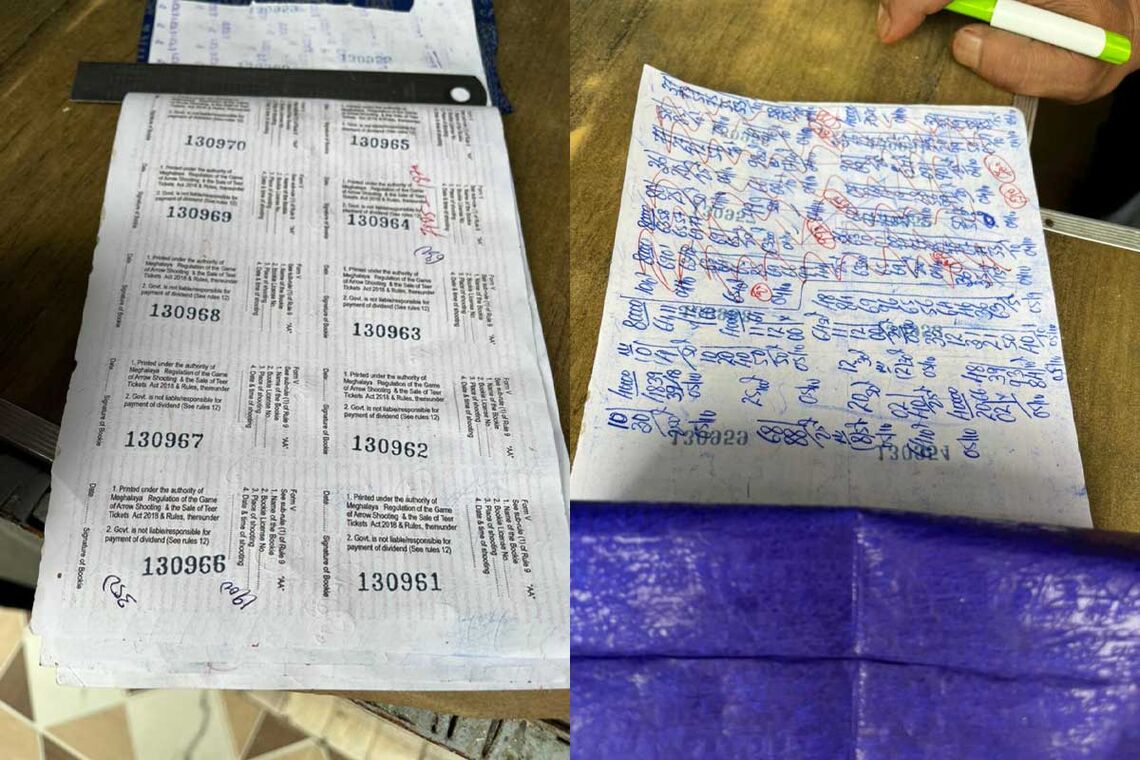

In the capital of the northeastern state of Meghalaya, Shillong, a crowd gathers every afternoon at the former polo ground. All morning, punters have been placing bets at kiosks lining the Police Bazaar, the city’s famous shopping district.

‘First Round: 55; Second Round 23.‘

The words are scribbled on big blackboards hanging in front of all the shops.

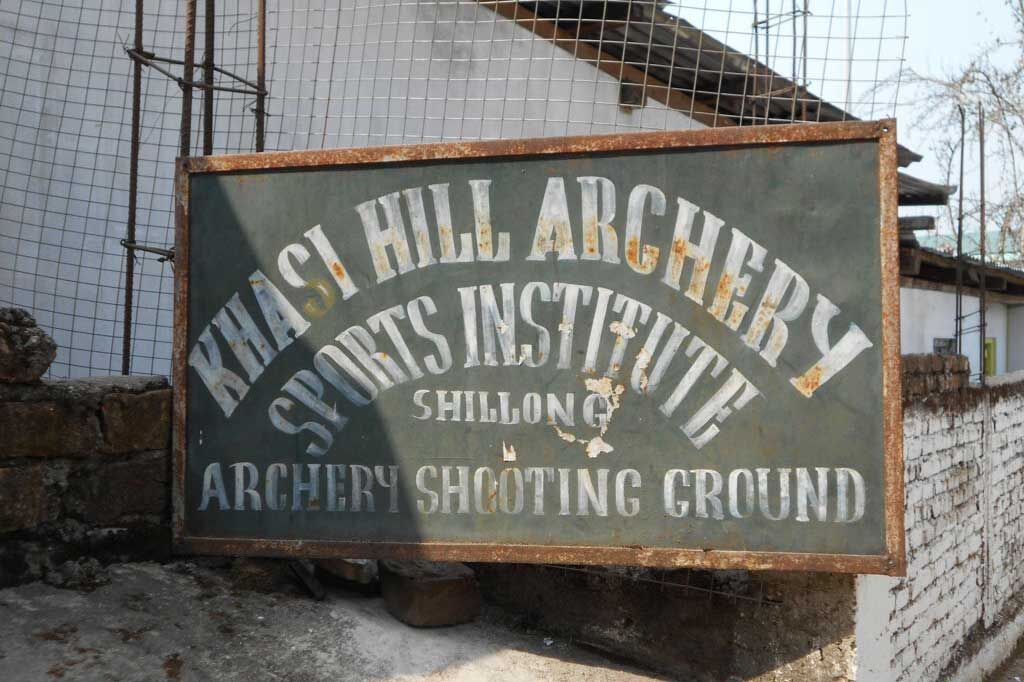

Shillong Teer is a betting game. Organised by the Khasi Hills Archery Sports Institute and practised by the local tribes for decades – at least – it’s the only legalised form of gambling in the state. (And governed by the Meghalaya Amusements and Betting Tax (Amendment) Act of 1982.)

Teer is the Hindi word for arrow.

There are other variants of this game – like Khanapara Teer and Juwai Teer – but Shillong Teer is the most popular, and there’s a lot of money at stake.

Divine direction

Teer is a game of archery, numbers and dreams.

The principle is simple – archers shoot arrows into a target. Punters pick a number between 00 and 99, inclusive, and the winner is whoever gets the last two digits of the total number of arrows that hit the target correct.

If the total number of arrows in the target is 692, then 92 is the winning number.

“I chose 22 and 68. This is the first time I have bought lottery tickets for this game,” says Pranab Medhi, a visitor in Shillong, who plans to head to the archery grounds later. “I have heard a lot about this intriguing game. So, I wanted to try my luck.”

Many punters believe that guessing the winning number requires interpeting dreams. No one knows how it started but the tradition has been passed down through the generations of the Khasi tribes.

If you see a snake in your dreams, pick the number seven. If you see boy and girl, pick 56 or 65…

…and if you dream of playing Teer itself, you will win no matter what.

The game

By 15h00 in the afternoon, the action is focused on the archery ground at Furlong Polo Road – a few 100 metres away from the polo grounds. It’s no longer a thoroughfare, it’s now an arena.

The place is thronged by local archers, bookies, officials and spectators, with more betting counters lining the boundaries.

“I have been visiting Shillong for business for a long time now and have seen how this game has grown over the years,” says Nipam Deka, a marketing professional based in Guwahati – in the neighbouring state of Assam – who watches the game anxiously.

“The blackboards in these shops have always allured me but I have never placed a bet. But today I thought I will try my luck, and I have placed a bet for Rs 100 on number 96.”

“Wish me luck.”

Rs 100 is about 1.2 USD.

Silence descends as 50 archers take their positions, squatting in a semicircle facing a cylindrical target made of bamboo placed 50 yards aways. On the referee’s signal, each of the archers begins shooting dozens of arrows at the target.

Two rounds – one of 30 arrows and one of 20 arrows – are played every day, and the game is contested between local archers from 12 different clubs across Meghalaya, identified by the different colours of their arrows.

Once all are shot, onlookers gather around the referee as he starts his count. Some punters wait outside the ground, others call the bookies chasing the winning number. There’s a strong online presence, too.

The winning number is 85 today. (There were 785 arrows in the straw.)

Medhi and Deka both lost their money.

A lifestyle and a livelihood

Banned by the state government in the 1970s, Teer betting is now one of the biggest sources of income for 1000s of natives in the state of Meghalaya.

A punter can earn up to Rs 80 (about 1 USD) for every Rs 1 (around a cent) wagered on a single round – or up to Rs 4,000 (about 50 USD) for guessing both rounds correctly on the same day. Onlookers here say that massive bets of more than Rs 5 lakhs (6100 USD) have been placed on a single number.

The industry supports around 5000 betting counters and 10,000 employees, according to local media.

“Teer is our daily bread and butter,” says Keshav Rao, one of the employees of betting kiosk. “Because it is in operation, we can make some money out of it. If this game stops, many people in Shillong will be jobless.”

Rao is paid Rs 400 (just under 5 USD) per day. The owner earns much more.

“The Teer business is huge, and lakhs [1000s] of people are involved with it either directly or indirectly,” says Saurabh Baruah, owner of the Sports Authority of India kiosk, which has sold Teer tickets for 30 years. “Through betting, this traditional game of the Khasi tribe lives on.”

“My father started this Teer lottery ticket shop and now I am the owner of it. And after me, hopefully my boys will continue the custom,” adds Baruah.

History of Teer

Archery has a significant role in the lives of the tribes of Meghalaya – the Khasi, Garo and Jaintia, each named after a range hills. The Khasi community constitutes nearly 80% of the state’s population.

Many say that archery was a gift from the gods to the Khasi people of this region, which was received by Ka Shinam (known locally as the ‘reigning goddess’), who passed the divine bow and arrows to her sons. The boys practised with these weapons and became skilled marksmen over time.

This tradition lives on in Meghalaya today, with Khasi boys learning the sport at a very young age.

“This is an ancestor’s game of the Khasi Tribe and has been played for a long time,” says Shri. Morningstar Jyrwa, secretary general of the Khasi Hills Archery Sports Institute, explaining the history behind it.

“It started as a friendly game between two brothers which led to fights and confusion as the arrows were of the same colour. So, the mother marked one of the arrows in white and the other without any mark, and this helped the brothers identify their arrows.”

First shot as a competition, the game spread through the villages and districts across Meghalaya, with people dividing themselves into groups and shooting at a target made of straw.

“People started betting with animals and livestock, while some would bet with money,” adds Jyrwa. “This is how the game of archery was played in those days.”

Pride

The bows and arrows play an important role in the lives of the Khasi people from birth to death.

Local archers, who come from the remote villages in Meghalaya, see it as a game of honour, pride and culture inherited from generations upon generations.

Called ka ryntieh, the Khasi bow is made of bamboo and is about five feet in length (about the average height of a Khasi man). The bowstring is made of split bamboo slivers, while the arrows are made of bamboo. Barbed arrowhead are used for hunting and plain points are used for Teer and competition.

Feathers of vulture, goose, crane or hornbill are used to fletch the shaft.

“I learnt the game from my father, and my father learnt it from my grandfather,” says Brigst Star, an archer who has shot in the Shillong Teer since 1993.

“I aim to shoot my arrows in Yaser Kham [getting 10 points] whenever I compete with my friends. If I get a chance, I want to compete in national championships.”

Like Brigst, many of his fellow archers want to take the sport further.

“Teer is part of our lives now,” adds Brijen Majaw. Most of the archers here earn around Rs 300 (a bit more than 3.5 USD) per day. “I love to shoot and so I take part in Teer and try to be part of this ancient tradition.”

The youth

Archery is in the genes of the people of Meghalaya.

“It’s great to see how these people have kept their centuries-old tradition through Teer,” says Pramod Chandurkar, secretary general of the Archery Association of India

“Their forefathers have used bow and arrow and the tradition continues. It still lives on.”

But in recent times, it’s not just the tribes of the region who have been taking part.

Teer has helped expose the sport of archery to young people.

Considering it’s integration with the local economy and daw, the state and national government is encouraging clubs to offer young people proper training, with the goal of producing modern talent from this ancient tradition.

“Centres run by the Sports Authority of India are polishing the talents born from the region,” adds Chandurkar.

”The hope is that these local players can become good archers if given the right opportunity.”